ARTÍCULOS

GENDER AS PATHOLOGY: DISEASE, DEGENERATION, AND MEDICAL DISCOURSE IN LATE NINETEENTH–CENTURY COLOMBIA

EL GÉNERO COMO PATOLOGÍA: ENFERMEDAD, DEGENERACIÓN Y DISCURSO MÉDICO A FINALES DEL SIGLO XIX EN COLOMBIA

GÒNERO COMO PATOLOGIA: DEGENERAÇÁO E CONCEITO MÉDICO NO FINAL DO SÉCULO XIX NA COLOMBIA

HANNI JALIL PAIER

1 Universidad de California, Santa Barbara, Estados Unidos. hjalil@umail.ucsb.edu

Artículo de reflexión: recibido recibido 14 /11 /11 y aprobado 24 /10 /12

RESUMEN

This article examines how Colombian doctors and public health officials during the last decades of the nineteenth century produced a body of knowledge about the health of the nation's citizens, using the language and authority of science to speak about a society in need of redemption and medical intervention. In these cases, gender became an essential component of elite and medical discourses. Medical doctors and hygienists described female identities either as potentially threatening and therefore degenerative to the nation's moral and economic fabric or as a 'civilizing force' through the mobilization of motherhood and the reification of the Colombian family as a regenerative site. The doctors and government officials here examined expected women to preserve the family as a unit and inculcate the values of order, hygiene and efficiency in the private sphere. If elite constructions of 'ideal' female identities mobilized women in their primary function as mothers, preoccupations with the control of 'public women' that upset public order or threatened the family unit rhetorically emphasized their deviance. In direct contrast to the feminine ideal, the construction of the feminine other emphasized moral transgression and sexual promiscuity.

Palabras clave: Medicine, Disease, Gender, Identity.

ABSTRACT

Este artículo examina cómo los doctores colombianos y los funcionarios de los servicios de salud produjeron, durante las últimas décadas del siglo XIX, un campo de conocimiento sobre la salud de los ciudadanos usando el lenguaje y la autoridad de la ciencia para hablar de una sociedad necesitada de redención e intervención médica. En estos casos, el género se convirtió en un componente esencial de la élite y de los discursos médicos. Médicos e higienistas describieron las identidades femeninas, bien como amenazas potenciales y degeneradoras de la moral y de la economía de la nación, o bien como una 'fuerza civilizadora' a través de la movilización de la maternidad y la reificación de la familia como un espacio de regeneración. Los médicos y funcionarios del gobierno colombiano examinaban y esperaban que las mujeres colombianas preservasen la familia como una unidad, e inculcaran los valores del orden, la higiene y la eficiencia en la esfera privada. Si las construcciones de la élite sobre identidades femeninas 'ideales' movilizaron a las mujeres como madres, las preocupaciones por el control de las 'mujeres públicas', que alteraban el orden público o el ideal, daban una imagen de amenaza a la unidad familiar. En directo contraste con el ideal femenino, la construcción de una otra femenina enfatizaba la transgresión moral y la promiscuidad sexual.

Key words: Medicina, Enfermedad, Género, Identidad.

RESUMO

Este artigo analisa o modo como os médicos colombianos e funcionários de saúde pública produziram, durante as últimas décadas do século XIX, todo um acúmulo de conhecimento sobre a saúde dos cidadãos desta nação, usando linguagem e autoridade cientifica para falar sobre uma sociedade que precisava de resgate e intervenção médica. O gênero tornouse um componente essencial nos discursos médicos e da elite. Os médicos e os higienistas descreveram as identidades femininas tanto como uma ameaça potencial e degenerativa para o tecido moral e econômico da nação, bem como uma 'força civilizadora' através da mobilização da maternidade e da reificação da família colombiana como um espaço regenerativo. Os médicos e funcionários do governo examinados no documento tinham a expectativa nas mulheres para preservar a família como uma unidade e que elas inculcaram os valores de higiene, ordem e eficiência na esfera privada. As construções da elite do 'ideal' para as identidades femininas mobilizaram as mulheres na sua função primária como mães, entanto que as preocupações com o controle de 'mulheres públicas', que importunaram ou ameaçavam a unidade familiar, retoricamente enfatizaram seu extravio. Fazendo contraste direto com o feminino 'ideal', a construção do feminino 'outra' enfatizou transgressão moral e promiscuidade sexual.

Palavras chave: Medicina, doença, gênero, identidade.

During the last decades of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth century societal and scientific notions of what was meant by 'civilization' in Europe, the United States, and Latin America acquired both racial and gendered dimensions (Bederman, 1995). After 1880, following social Darwinism and positivist thought, Colombian government officials, medical doctors and hygienists constructed 'civilization' as an explicitly racial and gendered concept, borrowing from wider scientific discourses and deploying these concepts in specific ways over the country's political, and social landscape. As public officials and doctors debated potential strategies and tactics to 'uplift' the nation they tried to make sense of Colombia's unique position as a predominantly mestizo, catholic, politically conservative, and modernizing nation. These men sought to craft a specific image of modernity in the eyes of both domestic and international critics. Thus, in the minds of Colombia's intellectuals, 'civilization' denoted a precise stage in human evolution, a stage that followed the more primitive stages of 'savagery' and 'barbarism.' Colombian officials and intellectuals imagined chaos, political instability, immorality, vice, disease, violence, and poverty as parts of 'barbarism' and 'savagery.' A state–sponsored discourse that focused on 'civilization' as one of its central ideologies was expressed through an increase in public health measures and social reform programs that proliferated after 1910 (Palacios, 2006). Government attention on 'la raza Colombiana' sought to explain and expose the symptoms and signs of physical degeneration, emotionality, suggestibility, impulsiveness, and instability, which purportedly characterized 'el hombre Colombiano' and hindered the nation's progress. In the minds of some Colombian elites the existence of this 'national pathology' helped to explain the violence and chaos of the previous century, historically expressed in eleven constitutions and sixtyfour revolts (Palacios, 2006).

The importance placed on the existence of a 'national pathology' to explain the country's inability to achieve political order and economic prosperity, expressed itself in the construction of a state–sponsored rhetoric of crisis. Literary scholar, Benigno Trigo (2000) analyzes how gendered and racial constructs were tied to notions of disease in Latin America. For Colombia, he argues that this nation's ruling classes medicalized race and gender in temporal and spatial contact zones. According to Trigo, '[the] parallel acquisition of ethnographic, anthropological, geographic and sociological knowledge, first clinical medicine and later laboratory and tropical medicine during the nineteenth and twentieth century configured differentiated disease networks' (Trigo, 2000: 10). Medically speaking, these networks constructed distinctions between diseases like hookworm, yellow fever, syphilis, criminal insanity, and degeneration not only on epidemiological terms, but also in culturally significant and socially constructed ways linking them to specific notions of gender, race and class.

As doctors medicalized definitions of disease, judgments based on class, gender, race, and sexuality interjected their discourse.1 Conceptually, gender entered the equation alongside sexual pathologies. In this context Colombian intellectuals and public officials constructed their own identities in relation to 'the evidently dangerous, disruptive, and hysterical nature of a sexually different body' (Trigo, 2000: 14). Set against a normative male identity, peasants, urban laborers, women and their bodies were imagined in a state of perpetual crisis. As Colombia's intellectuals portrayed part of the nation's population in this way, they identified two key differences that posed a threat to the stability of their society: sexual and racial difference. To tackle this perceived threat, the government instituted programs of public health and disease control, describing the country as a geographically daunting region, its lower class citizens as vice–ridden, racially handicapped, and psychologically unbalanced; prostitutes and working women as victims of a hysterical unnerved body and a degenerative agent for 'la raza Colombiana.' In the minds of these individuals, Colombia appeared to be in crisis, a country in need of strict management and government regulation of individual bodies and collectivities identified as different and potentially dangerous.2 The management and regulation of 'diseased' bodies, where the latter included more than biology, permeated Colombia's national discourse. Positivism, imbued the country's scientific and political discourse; shaping the construction of gendered identities through the creation of 'ideal' and deviant female identities.3 This article provides specific examples that contextualize the discursive creation of gendered subjects in Colombia through an analysis of some of this nation's medical texts and public health measures. The creation of a feminine ideal and consequently the construction of a deviant other, although deployed for different purposes gave Colombia's official discourse and medical project a visible gendered dimension.

The Birth of Modern Medicine: Women in the Medical Discourse

But, oh the power of intelligence! Glory to the immortal Pasteur, who dedicated his genius to the biological study of beings long ignored due to their microscopic dimensions. He has opened new horizons, and whose discoveries places in our hands antiseptic procedures. The success to which we owe all of the triumphs and advacements in surgery, but especially in the field of obstetrics. Dr. José Tomas Henao, 1893

The late nineteenth century witnessed the progressive expansion and consolidation of the medical sciences. In Latin America, this process was generally a function of the institutional growth of science that occurred throughout between 1890 and 1930; understood by historians of medicine as a by product of the larger revolution in bacteriology. As the nineteenth century progressed, theories that relied on miasmas to explain the spread of disease were brought into question; older theories were gradually discredited by recent discoveries spearheaded by French chemist Louis Pasteur and German physician Robert Koch that led to the subsequent emergence of germ theory (Tomes, 1998). However, this revolution in bacteriology did not immediately lead to a dismissal of miasmic theories. Challenges to older theories were part of a gradual process, so that even towards the end of the century, hygienists and sanitation officers still emphasized the 'detrimental' effects of foul airs (Márquez, 2005). Even with their gradual adoption, germ–based theories revolutionized the medical field. By the turn of the century medical professionalization was well underway. In 1867, the Medical school at La Universidad Nacional in Bogotá opened its doors, helping to foster the study of Medicine in the country. Five years later in 1872, at Universidad de Antioquia followed suit and a year later (1873), Bogotá's Sociedad de Medicina y Ciencias Naturales (hereafter referred to as the SMCNB) held its first annual meeting. Under the SMCNB, the Academia Nacional de Medicina, brought together Colombia's most prominent physicians and scientists and commenced monthly publication of articles, treatises and medical studies in the Revista Médica de Bogotá (Obregón, 1992).

The professionalization of medicine in Colombia helped to reorganize medical practices in the country. After the establishment of the Junta Central de Higiene (hereafter the JCH) in 1886, the lines between private medical practice and official municipal, regional, and national positions on hygiene and sanitations boards quickly became blurred. In their new public roles, doctors became key players in the consolidation of a prosperous and healthy society, their role often extending beyond the regulation and control of physical illnesses. Doctors offered and prescribed solutions that incorporated the moral and social dimensions of vice and disease. In this way, doctors and hygienists were closely linked to public policy and to the legislation of morality by a consolidating state. This highlights interesting trends in the professionalization of medicine, particularly in relation to women as patients of incipient medical fields like obstetrics and gynecology. In the case of Colombia we may ask how doctors treated and related to women, whose social significance and identity was primarily constructed in terms of their role as mothers of the nation. In Colombia, this emphasis on the maternal role of women sought to mobilize them as moral arbiters of the nation. These 'ideal' women were in charge of moralizing society and helping to advance order and progress in a nation that needed to rely on their help in crafting 'ideal' citizens. In addition to their symbolic role as mothers and their mandate to morally uplift society, women were quite literally 'madres de la nacion.' Their bodies were directly responsible for the regeneration of the race and hence physically responsible for reproducing future citizens on whose back the nation's progress would be forged.

By the late nineteenth century, a new generation of medical students looked towards two sub–fields of medicine, gynecology and obstetrics; set under the context of a revolution in bacteriology, the incipient consolidation of modern medical practices, and a rise in the publication of medical journals like Revista Médica de Bogotá, Revista de Higiene, Boletín de Medicina del Cauca, and Revista Repertorio de Medicina y Cirugía. The publication of these journals achieved two objectives; first it created a new forum where medical professionals could engage in scientific discussions and report their most recent findings and experiments. Secondly, it helped foster regional, national and international networks of scientists. 4 Women and their bodies appeared frequently in these journal articles; their presence suggested societal preoccupation with the 'female question,' denoted a medical concern with defining the role women should play in forging the new nation, and mirrored the formation of gynecology and obstretics as sub–fields of medicine. As patients and subjects of study female patients figured prominently in the pages of the Revista Médica de Bogotá. As instrumental players in the regeneration, regulation, and sanitization of the Colombian family they were addressed in their role as mothers and moral arbiters of the nation in the pages of the Revista de Higiene. Additionally, what has thus far been referred to as the feminine other, embodied in the prototype of the prostitute as a licentious, fallen woman, figures prominently in the latter; however the latter will be analyzed in a separate section of this article.

Between 1893 and 1894, issues no. 182, 183, 185 and 186 of the Revista Médica de Bogotá, featured a total of nine articles, studies, or advertisements related to gynecology, female anatomy, and what contributors defined as gender–specific conditions under such titles as, 'Glycerin and Birth,' 'Syrup Gelineua: for nerves and menstruation,' 'Intrauterine injections,' 'Ovariectomy' and 'Obstetric Antisepsis' (Revista Médica de Bogotá, 1893–1894). It should be noted that while the re–occurrence of such articles and pieces may at first seem trivial, this journal was printed on a monthly basis and that in the four issues mentioned articles related to women's health appeared on average two times per issue, while pieces that dealt with other medical issues appeared less frequently. Medical preoccupation with women tied to the rise of gynecology and obstetrics helped institutionalize the regulation of women's bodies and pitted incipient medical procedures and practitioners against 'alternative' medical practices such as midwifery. Colombian doctors Medical published medical treatises during this period that described the dangers of seeking the services of unlicensed doctors, charlatans, curanderos, and midwives. Doctors like Jose Tomas Henao who frequently published in various Colombian medical journals, pointed towards midwifery and other alternative medical practices as a threat to the modern medical profession. For Dr. Henao and other practitioners of western medicine this confrontation featured 'science and modernity' against the 'superstition and ignorance,' represented by the 'arbitrary' and 'detrimental' practices of the local midwife (Henao, 1893). The repercussions of this debate extended beyond the use of scientific methods and modern medical practices in lieu of so–called superstitious and non–scientific practices. The juxtaposition of this debate between western medical sciences and alternative medical practices has inherent racial and gendered overtones. In the case of midwifery the gendered dimensions of this discourse pitted male medical practitioners against female midwives, modern medicine (an almost exclusive male domain at the time) against midwifery (a female–dominated trade), 'scientific objectivity and rationality' against what male doctors constantly referred to as female–controlled and outdated intuition.5

Attacks on midwifery, heralded by a male–dominated scientific community ultimately led to government attempts to regulate this profession. Only midwives with official training from a sanctioned medical academy could 'legally' perform their trade and of course only under the supervision of a male medical doctor. In 1895 the 'Reglamento de la Junta Central de Higiene y Ministerio de Instrucción Publica' mandated certified medical doctors and surgeons to supervise midwives and required female practitioners to obtain proper licenses (Revista de Higiene, 1895). In this attempt to regulate a practice that doctors trained in western medicine defined as a threat, midwives without proper licenses were often discredited and blamed for high infant and maternal mortality rates. With obstetrics and gynecology as incipient medical fields, childbirth, a traditionally female–dominated sphere came under official attack. As a male–dominated field during the last decades of the nineteenth century, western medicine tried to define the boundaries of acceptable medical practices. It is important to note that although official policy called for the regulation of midwifery, the number of western–trained doctors was limited, and concentrated in the nation's major urban centers. For this reason, midwifery could not be completely marginalized or discredited; at best the medical establishment could only attempt to regulate it.

Women as Patients and Subjects of Study: The Body and the Uterus in Crisis

Medical practices helped to delineate gender differences and prescribe social positions for men and women within Colombian society. The simultaneous control of female bodies and their moral behavior sought to prevent societal breakdown. In large part due to gynecology and obstetrics, the institutionalization of the female body extended its reach beyond the doctor–patient relationship, creating a dialogue that described female sexual conduct in relation to their reproductive functions and linked female bodies to disease. The link between corporeality and disease brought female reproductive organs under close scrutiny, with particular emphasis on the uterus.

Medical treatises on the uterus as a key organ in female anatomy and physiology extend as far back as Classical Greece. Hippocrates was among the first doctors to link the uterus to notions of disease and introduce hysteria to medical terminology. From the Greek, hystera (uterus), this term referred to a medical condition caused by disturbances and irregularities in this organ's functions. Hippocrates explained this condition describing the uterus as a free–roaming organ, wandering around the body, causing imbalances and disturbances that were typically expressed in nervousness, anxiety, weakness, loss of appetite, and irregularities in the menstrual cycle. This helped categorize female patients as perpetually ill and in a state of constant crisis. The obvious linkages between uterus and disease had wide repercussions for women's health care and the increased medicalization of biological functions. Linked not only to disease, the uterus became a site connected to the female life cycle, the role of motherhood, and the regeneration of the human race through birth.

Dr. Juan B. Gutiérrez, doctor at the Hospital de San Juan de Dios in Bogotá, documented a strange medical case study on the pages of Revista Médica. Eighteen–year old cook, Aurora Muñoz, from Chiquinquirá, entered the maternity ward on May 31, 1898. According to Gutiérrez's, shortly after her first sexual contact, she reported heavy bleeding followed by episodes of severe pain to local doctors, in addition to these symptoms initial reports documented ' vomiting, vertigo, anorexia, and muscle spams,' after some deliberation the doctors in charged of Aurora said she was pregnant (Gutiérrez, 1898). But in spite of the diagnosis, the patient continued to experience regular, monthly periods, albeit the flow varied in its intensity as the months progressed. Five months afterwards, she reported 'slow and tenuous movements' on her right side, presumably described by Aurora as 'fetal movements.' After local doctors conducted further medical examinations, they offered a second diagnosis. Aurora was diagnosed with an 'extra–uterine pregnancy.' After her condition worsened, 'mortified by pain and continuous muscular contractions,' Aurora decided to travel to the nation's capital and seek what she described as expert medical attention. At the facilities of the Hospital de San Juan de Dios, a team of doctors initiated a series of examinations and 'exploratory exams,' in order to access the accuracy of the previous diagnosis. Initially, the results suggested a misdiagnosis. Aurora's condition did not fit the diagnosis given by Chiquinquirá doctors; there was no 'extra–uterine pregnancy', the mass described by the patient was a tumor. Armed with this new discovery, Bogotá's doctors submitted the patient to additional tests. On June 3, 1898 at 2:00 p.m. in front of an audience of students Aurora's body became a site of medical exploration and scrutiny, and her anatomy the object of the male medical gaze. Dr. Barreto 'inserted his hand through her rectum until he reached her abdominal wall, he then was able to feel her uterus and ovaries with ease and without epidement, unable to locate any sign of the tumor.' Given that the team failed to find any foreign mass, they concluded that, 'this pregnancy was then the result of hysteria.' (my emphasis: Gutiérrez, 1898: 45).

Gutiérrez's report ended with a telling side note. According to the author, 'when the patient regained consciousness the team led her to believe they had extracted the tumor.' Given Aurora's medically presumed proclivity to suffering from 'episodes of hysteria', Gutiérrez closed his report stating that:

We have transcribed the preceeding narrative, remaining faithful to the patient's own words, but we do not trust that she has been completely truthful, we venture to ascertain that she had prior knoweldege about what happens in these sort of cases... such is her interest in making us believe that she was pregnant, that moments before proceeding with the anesthesia she insisted she was certainly pregnant (Gutiérrez, 1898: 46).

This case, though exceptional in the historical record gives us a glimpse into medical trends in the incipient field of gynecology and obstetrics heretofore mentioned. First, Aurora's body became a site of regulation, control and scrutiny. The language used to describe her symptoms framed Aurora as a patient undergoing a medical crisis. Second, doctors filled the report with skepticism and doubt in light of they perceived as Aurora's unreliable testimony. Gutiérrez continuously questioned the accuracy of her statements. He questioned Aurora's ability to describe her symptoms, her medical needs, and her capacity to 'know' her body. As a woman, Aurora's gender tied her to medical assumptions about a lack of expertise and education. Her gender also allowed for the doctors assigned to her case to assume she suffered from hysterical tendencies and thus placed her statements under scrutiny and rhetorically dismissed the possibility of a medical misdiagnosis, at least among Bogotá's medical doctors. Her symptoms: vomiting, loss of appetite and vertigo allowed for medical speculation and a possible misdiagnosis, yet Aurora was at fault, not the team of doctors that examined her. After the doctors at San Juan de Dios ruled out the possibility of a pregnancy or tumor, the report's concluding remarks explained away any irregularities of Aurora's case by emphasizing her recurring episodes of hysteria. Access to original reports filed by Chiquinquirá's doctors and Aurora's testimony would provide important nuances to the narrative, reiterating or perhaps even contradicting facts taken from Gutiérrez's report. In spite of these silences in the historical records, Gutiérrez's report still allows us to take a glimpse into late nineteenth–century medical attitudes and practices in relation to female patients and the regulation of their bodies.

Physical and Moral Regeneration: Gender, Sexuality and the Colombian Family

We have only one point left to analyze: can morphine addicts be cured? Yes, as long as they place themselves under the care of a capable doctor, and they are exposed to a woman whose sweet demeanor can harmonize his energy and strong will, capable of imposing her will, to the patient and to his family Dr. Manuel N. Lobo, 19 de Julio de 1899

While female patients and their bodies became subjects of study, the family as one of the primary vehicles of social reproduction and microcosm of the nation also came under scrutiny. As a unit, the family was connected to notions of disease, where all the problems of modernity seemed to come together and threaten it. Throughout Latin America, the traditional family seemed increasingly at risk during the first decades of the twentieth century. In Colombia the growing presence of women in the work place, prostitution, illegitimacy, alcoholism, and substance abuse that accompanied industrialization, migration, urbanization and poverty idealized the family as a site of moral and physical regeneration. Medical doctors and government officials often invoked women, in their role as 'angels of their homes' and religious faith to lead by example and diffuse principles of morality to a nation in need of salvation.6 Invested in the construction of 'ideal' citizens to 'civilize' and ensure the physical and mental well being of the nation, doctors and hygienists enlisted women as moral arbiters of the nation and guardian angels of the Colombian home. These women would ideally play multiple roles in public health campaigns and prophylactic efforts, particularly in governmentsponsored campaigns against alcoholism. As mothers, wives, and household managers each of them was directly responsible for their family's welfare. If every woman were successful in her attempt to maintain a household free from vice, dirt and disease then collectively Colombian society would benefit from her efforts.

On July 19, 1899 renowned physician Manuel N. Lobo, during an administrative section of the Academia Nacional de Medicina, addressed an audience of medical students and colleagues. The central theme of his speech was morphine addiction. Speaking to an audience of experts and fellow scientists, Dr. Lobo's opening statement offered tribute to science and civilization as beacon lights for the nation. To him:

Modern civilization, unjustly treated, has brought us immense benefits. Humanity, in its struggle for survival, everyday wins battles that result in the acquisition of a greater good. Wisemen, inside their studies and laboratories, take nature's secrets, with which they are able to improve men's lot and improve his quality of life, in this [existence] which many have called a valley of tears (Lobo, 1899: 374).

Modernity and civilization played prominent roles in his speech. He immediately set the stage for what rhetorically followed. Scientists, doctors, and men of intellect would lead Colombia into the modern era; they held the key to scientific advancement and hence to the re–vindication of the race.

But despite his initial enthusiasm, Dr. Lobo warned his audience against the potential misuse of scientific discoveries by 'enemies to intelligence,' and in this particular case he referred to abuse of morphine, intended to be an asset to alleviate pain, ' Unfortunately, evil always intermingles with good. The great utility of morphine has been tainted by the prejudices that follow its abuse.' He went on to describe to the effects of this dependency. First the morphine addict's energy decreased, his brain lost the ability to work and was therefore destined to malfunction. As his energy waned, the addict lost his color, was easily excited and fatigued, he had no other thought than: the injection. Unless immediately administered, the patient lost his patience, became taciturn and sought solitude in order to inject himself. If he lacked the morphine he became exasperated and begged. If he failed to obtain his aim, he became enraged, and lost every sense of duty and social convention. He turned into an animal, 'incapable of any reason.' He lied, he stole, 'he'd be capable of any base act to get a hold of morphine.' At this point in his addiction, 'the morphine addict turned into a repulsive member of society. His memory loss, his predicliction towards unproductivity, his sad and irritable character, his abandon to manners and propriety, make his company a nuisance...he forgets his social and familial duties' (Lobo, 1899).

Among women, morphine addiction led to their dishevelment and their lack of personal care, theor addiction 'was even more repulsive among women, since they were the angels of their homes and mothers of our nation.' They lost all of their desire to please and comply, ' so natural among them: they care not about society, about their husband, or children.' The morphine addict's shame and their lack of affective ties or morality were led to truly criminal acts, which drove the latter to prison, the asylum or their grave. Those who witnessed this condition, agreed that, ' these degenerates were individuals easily persuaded by morphine and were almost incurable from their addiction once it acquired.' The individual that fell prey to excess was weak and therefore susceptible to vice (Lobo, 1899). The gendered dimensions of this discourse, reached a climax in Dr. Lobo's speech as he went on to equate the degenerate addict to the hysterical woman:

[Morphine addicts] suffer from the same ailments as hysterical women, neurasthenics, and in general, unbalanced people. Their physical weakness is an expression of a low moral or intellectual capacity... these enemies of the race come into our home because we willingly open the door. And thus cause incalculable harm (Lobo, 1899).

If women were imagined as guardian angels and keepers of the nation's morality, then the responsibility of closing the door of their households to these degenerative forces and enemies of the 'la raza Colombiana' also rested in their hands. Yet, their presumed hysterical tendencies could also threaten the social order.

There were two reasons that predisposed patients to addiction, 'among them, we list the two which we consider are the most important ones, and over which man has control: hereditary degeneration and a poor education over the will.' Society's and an individual's moral foundations were the result of hereditary factors and education:

At birth we posses certain tendencies, as these develop they will later make–up our character. If these tendencies are good, a childhood illness can without a doubt interrupt its development, just like a poor education may also make one suceptible to the same degeneration. We should however acknowledge that to an important degree all moral perversions are necesarilly hereditary (Lobo, 1899).

The construction of moral perversions as both hereditary and yet changeable through education, gave women two crucial roles within Colombia's medical discourse. First, as biological agents, their bodies and reproductive capabilities came under societal and medical scrutiny. Secondly, as moral agents and angels of the home, they shared in the responsibility of educating their children, inculcating moral principles and ensuring that their home became a site of regeneration rather than degeneration.

Citing Herbert Spencer, Dr. Lobo listed the moral and intellectual motives that potentially drove individuals to morphine addiction. He highlighted the importance of a solid moral education as he asserted:

One of the perfecting qualities of the ideal man, says Herbert Spencer, lies in his ability to have supremacy over his will and his actions...Without succumbing to our impulses, without letting our desires dictate our actions, but rather mantaining a just balance... by which each and everyone of our decissions shall be discussed and made with complete serenity (Lobo, 1899).

Comenting on the bases of recovery, Dr. Lobo concluded his speech restating that it was up to women in their influential roles as mothers, wives and relatives to set the foundations for, ' that education of the will we gave lost' (Lobo, 1899). Dr. Lobo's closing statement shows the ways in which medical doctors and intellectuals at this time constructed the Colombian family as a locus of social reproduction and a place where societal ills could in the best cases be eradicated, and in the worst reproduced. In their positions within this institution, women played a central role in the preservation of the family's spiritual and moral health and consequently its physical welfare.

Legislating Morality and the Limits of Sexual Promiscuity: Public Health, Venereal Disease and Public Women in Bogotá 1880–1930

Protitution is a vice, a disease, an evil. Let's fight it! Let's study ways to supressed it, if it is possible. Double the obstacles so that woman may not prostitute themselves, raise sanctions to avoid their fall, pass laws to protect women workers, let's educate and instruct deviant women. At last with laws and scanctions try to diminish the number of women that fall. Revista de Higiene, 1921

Public debates over the regulation of sexual commerce in Bogotá between 1880 and 1930 need to be interpreted a contextualized as part of a larger global moment in social reform movements, international activism, and campaigns against venereal disease. Debates over the regulation of prostitution, the politicization of leisure, pleasure, and disease varied across geographical boundaries, taking on a number of specificities and nuances unique to the society's that engendered them, and yet local and national specifics belonged to a movement with transnational dimensions that encouraged cross–national debates and conversations among doctors, hygienists, activists and public officials. 7 Colombian doctors and hygiene specialists drew inspiration from reform programs enacted in France, England, the United States and Argentina. National hygiene boards sent out delegates and representatives to several international conferences. Their participation in these venues speaks to the transnational quality of public health campaigns and sanitary reforms during this time period. The implementation of public health campaigns, epidemic control, and disease prevention programs in Colombia meant to demonstrate the state's capacity to guarantee the health of its inhabitants. Recognized at home and abroad, the government's ability to effectively contain disease was an important component of Colombia's modernization efforts, conversely its failures tarnished the veneer of modernity that state officials sought to convey.

At this time, Colombian doctors, hygienists and public officials expressed concern over official definitions of proper and deviant femininity. They sought to delineate the boundaries of appropriate sexual behavior and wanted to address the threat of venereal disease and its proliferation. During the last decades of the nineteenth and the initial decades of the twentieth century, several Latin American countries instituted regulatory measures in an attempt to control and counteract the spread of sexually transmitted infections. Government–sponsored programs instituted anti–venereal campaigns, creating public health and sanitation boards in charge of sponsoring prophylactic measures. These included the establishment of hospitals in charge of providing adequate medical treatment to infected patients, especially 'way–ward' women. In addition to disease prevention, medical efforts to regulate the spread of disease brought the prostitute and her body under close medical and legal scrutiny, requiring women who engaged in sexual commerce to register with the local hygiene and sanitation boards, undergo weekly medical examinations and carry a certificate of health. Accordingly, all unregistered prostitutes would be subject to arrest during official police raids. In the minds of some Colombian doctors the threat of widespread venereal infections that threatened their society with collapse and sent its inhabitants down a path of perpetual crisis, justified bringing prostitutes and the bodies of suspect women under close inspection. This section examines how debates over regulation or repression of sexual commerce unraveled in the minds of prominent doctors and left a mark on medical discourses about female sexuality at this time.

The creation of ideal female identities that imagined women as the nexus between family and nation, meant that women were not only enlisted as moral arbiters, and that their role as mothers elicited considerable attention in the hands of Colombian doctors and public officials, but also that women who did not embody this model–identity fell short of this ideal. Debates over the regulation, tolerance, or repression of sexual commerce were central to the creation of a female–other embodied in the degenerate, deviant and sexually promiscuous prostitute. The prostitute became a figure thought to be antithetical to constructs of ideal femininity centered on notions of motherhood, obedience, religiosity, resignation and morality.

By overlooking the complexities inherent in processes of identity formation and social realities, medical doctors and government officials helped to reify a dichotomy between ideal and deviant femininities, helping to maintain and sanction spaces where males could channel their desires in regular visits to brothels and encounters with 'fallen women.' These 'fallen women,' in turn safeguarded decent and virginal women from potential sexual predators. For some, prostitution was a 'necessary evil.' These women and their bodies helped to prevent sexually adventurous men from creating greater threats to the social order. In Colombia, like in other Latin American nations, discussions over the regulation of prostitution were laced with moral, hygienic and political concerns. Much like the moral dimensions of this debate reinforced the creation of a binary juxtaposition between 'fallen woman' and 'angel of the home,' the institutionalization and medicalization of female bodies, as sites of control and regulation, combined two distinct ways of imagining the body as a site of crisis. On the one hand, the body of the ideal woman and mother gave birth to children, family, and nation becoming a site of regulation and control; while on the other the prostitute's body became a site where money, pleasure and venereal disease came together to create a deviant identity, equated with filth, immorality, and infertility.

In Bogotá, debates that centered on prostitution as a social ill led to the emergence of multiple mechanisms of vigilance, control and regulation. These mechanisms emerged gradually between in the latter decades of the nineteenth and early decades of the twentieth century. Initial arguments focused on the degenerative effects of legalizing sexual commerce. These arguments posed that the legalization of prostitution was a threat to the nation's morality and to family integrity. But, the rapid spread of venereal disease, coupled with the recognition that rates of prostitution were on the rise, in spite of moralization campaigns, led reformers and public officials to consider alternative programs, promoting the establishment of a government–sponsored system of regulation. While adherents of this new approach acknowledged that prostitution could not be eradicated and was therefore in need of regulation, they again emphasized morality and the eradication of vice inside the home, once again looking towards the Colombian family as a site of physical and moral regeneration.

During the last two decades of the nineteenth century, as Colombia's profits from coffee and tobacco exports began to rise, Bogotá experienced a period of sustained population growth and urbanization. Between 1870 and 1895, Bogotá's population more than doubled from an estimated 40,883 thousand to an estimated 95,813 thousand inhabitants. The emergence of small industries and the inception of a nascent brewing industry in Bogotá through Cerveceria Bavaria, Colombia's first large industrial complex, created a demand for unskilled labor, fueling rural to urban migration contributing to the transformation of Bogotá's physical landscape (Sowell, 1992: 21–22). This process of urbanization and population growth exacerbated living conditions for Bogotá's poor. Public officials worried about overcrowding, poor hygiene, and the municipality's inability to provide adequate infrastructure and sufficient jobs for migrants. Under these conditions of rapid demographic and social change, public officials complained about prostitution's increased visibility and sought solutions that would help regulate the spread of sexual commerce, vice and disease.

Official treatises on public hygiene and sanitation in Bogotá ranged from reports on the local slaughterhouse, trash disposal and street conditions, reports on local cantinas, bars, and chicherias, to reports and studies on vagrants and prostitutes. In 1893, Dr. Pablo García Medina, active member of the JCH gave a report to the National Academy of Medicine emphasizing the necessity of enacting regulatory measures to sanitize the city's slaughterhouse (García Medina, 1893: 245). Transforming Bogotá's physical landscape, entailed making infrastructural improvements, extending public works, and policing the habits, customs, and behaviors of the city's inhabitants. The regulation of prostitution and prophylactic campaigns against syphilis and other venereal diseases were important components within this larger and more expansive sanitary movement. After the creation of Bogotá's SMCNB in 1873, the Revista Médica de Bogotá began its monthly publication. Initially, contributors to La Revista reproduced French medical studies and treatises on prostitution and venereal disease, mostly translations and excerpts from French doctor and hygienist, Jean Alfred Fournier.8 Between 1873 and 1886, treatises on prostitution and preventive campaigns on venereal disease were almost exclusively translations of professor Fournier's work. After 1886 under the auspices of the JCH, Colombian doctors, medical students and hygienists began to publish their own findings based on government sponsored studies and commissions. The increase in the number of studies after 1886 coincided with the creation of the JCH, the propagation of venereal disease, and the city's current unsanitary conditions all of which presented worrisome challenges to local authorities.

On May 29th of that same year (1886) Bogotá's Municipal police director, Rufino Gutiérrez, wrote a letter to the SMCNB, asking this organization to provide the municipal police with special instructions on how to enact moral and sanitary measures that would help eradicate, 'the vice and immorality that today invade our city streets.' In response to this request and to other official petitions the SMCNB established a number of commissions dedicated to the study of several of the city's hygiene and sanitary conditions. These commissions addressed Bogotá's bread quality, street cleanliness, vagrants, taverns and the sale of alcohol, and prostitution (Gutiérrez, 1886: 305). Dr. Aureliano Posada headed the commission on prostitution. Trained professionally in Paris, by 1886 Posada was a renowned member of Colombia's medical establishment. He taught medicine in Bogotá and Medellín and was an active member of the SMCNB and the JCH (Obregón, 2002: 167). Posada's report, 'Report on Prostitution,' highlighted morality as central to the ongoing public debates surrounding prostitution and sexual promiscuity. He claimed that sexual drives and instincts were considerably more developed in men than in women, confirming Catholic precept that de–emphasized the existence of an intrinsic female sexual desire. His assertions implicitly reasserted the construction of 'ideal' women as submissive wives and mothers, models of virtue and chastity. For Posada, 'the primary cause for this infamous profession [prostitution] was the misery suffered by young woman, who are seduced and abandoned to their fate our urban centers.' In addition to exposing Colombian society to progressive moral decay, prostitution threatened the social order, and the nation's future by exposing Colombians to the hazards of venereal disease and physical degeneration (Posada, 1886: 326).

As debates over the existence of sexual commerce generated fears and apprehension among Bogotá's ruling class, the threat of moral and physical degeneration, explicitly stated in Posada's report, fueled ongoing discussions over the necessity of instituting measures to regulate prostitution. Fears of what seemed like the unstoppable spread of venereal disease filled the minds of Colombian doctors and hygienists and were thus translated into a language that imagined a society in crisis. This crisis meant that prostitution could trap Colombia's youth leading them and the future of the nation into a chaotic and tragic end, aptly described by Dr. Posada in the pages of his 1886 report:

Prostitution is on the rise, each day it grows more daring and cynical, exposing itself publicly, promoting the worst attacks on morality, offending decency, attracting and imprisoning in its nets innocent young men and women, throwing the latter into an abyss of corruption. Degrading them, both physically and morally, turning them into unproductive and dangerous members of society; adults without the energy or will to resist temptations, causing thus the loosening of sacred familial ties (Posada, 1886: 318).

The public face of sexual commerce, the rapid spread of disease and the proliferation of brothels and chicherias on Bogotá's landscape, threatened the nation's capital with moral and physical decline. It turned its youth into dangerous elements and unproductive adults, and ultimately prompting the dissolution of sacred family ties. Posada's portrayal of a society on the verge of collapse showcased a language informed by invogue theories of degeneration and moral decay. His preoccupation with the dissolution of sacred family ties, reiterated the importance given to the family as a site of regeneration in Colombian society, but his warning also imagined the family as a site equally susceptible to harboring degenerative forces and prone to disease.

Infused with pessimism, Posada's conclusions offered what he imagined was a grim but realistic view of Bogotá's future. Since prostitution was an intrinsic social ill in large urban centers and it was virtually impossible to stop its spread or completely eradicate it–it should at the very least be regulated. As a result of Posada's report, the city's mayor mandated the establishment of a public service dispensary for venereal disease and syphilis at the Hospital de San Juan de Dios, with the goal of examining 'public women' sent there by municipal authorities. After undergoing medical examination, hospital doctors would issue a certificate of health, certifying the prostitute's current medical condition and documenting a date for future inspection. In cases where venereal infections were detected the prostitute would remain in the hospital and undergo medical treatment, before she could return to her trade (Obregón, 2002: 163). These regulatory measures placed the burden of prophylaxis on the prostitute, equating her body with disease and degeneration, targeting the prostitute as an agent of contagion and for the most part ignoring the role of male solicitors– factoring them out of the prophylactic equation.

Posada's statements and his position vis–à–vis the regulation or tolerance of this 'social ill,' provide evidence of a tension between the need to regulate sexual commerce to prevent the spread of disease, and the enforcement of 'morality and good customs,' so central to a society where Catholicism and conservative political ideologies dominated the social landscape. While Posada sympathized with proponents of government regulation, particularly as a means to improve Bogotá's public health and sanitation, this did not prevent him from condemning prostitution as inherently immoral. Comparing the state of Bogotá's moral customs to major European metropolises, he asserted that:

Because of our social ways...immorality, among us, has not reached great proportions and our customs openly contradict the tolerance required for regulation of the trade...but since it is not possible to stop prostitution and consequently the general spread of venereal disease and syphilitics, it is the government's duty in other to advance hygiene to authorize the trade, but regulated it in the best and most convenient way, so that it can be less threatening to the current social order (Posada, 1886: 333–334).

This dilemma and the tensions that continued to be expressed within the medical discourse meant that while regulation appeared to be the one of the only practical solutions, eradication and repression did not completely cease to occupy an important position in the minds of Colombia's public officials and social reformers.

In 1892, after a six–year tug of war between Bogotá's municipal police authorities, public health officials and prostitutes, Cundinamarca's police solicited instructions from the JCH, in hopes of improving regulatory measures already in place and of enacting more effective prophylactic campaigns. This time around, the JCH appointed Dr. Gabriel J. Castañeda to fulfill the police department's request. In his report, Castañeda, professor at Bogotá's Universidad Nacional and founding member of the SMCNB, described the various challenges that faced the medical profession in the treatment of syphilis and gave a detailed account of the four principal stages of this disease. Additionally, he described what he saw as conditions that went hand in hand with this disease, 'misery, inability to work, additional strains on the public assistance budget, sterility, infant mortality, and racial degeneration.' Syphilis and its detrimental consequences on the health of the nation, continued to threaten Colombia's progress, infecting the nation's future with a disease that would incapacitate its workers, overwhelm programs of public assistance, waste the country's resources and lead to its general misery (Castañeda, 1892).

Castañeda openly criticized the current state of regulation, which did not extend beyond the registration and treatment of prostitutes in Bogotá's local medical dispensaries. He advocated for stricter and more expansive measures that would ensure tighter control over the spread of venereal disease and sexual commerce in Bogotá. His suggestions included government oversight over brothels, cantinas, and taverns, the creation of a special police force exclusively in charge of regulating prostitution, and the allotment of municipal funds to improve the quality of medical care and treatment offered at the Hospital de San Juan de Dios' syphilis ward:

In spite of Castañeda's petition for stronger regulatory measures, the JCH and municipal authorities did not reach a consensus and hence did not implement any of his suggestions. Castañeda's critics attacked his petition presenting two main arguments; some argued that the petition restricted personal and individual liberties, while others argued that it his suggestions would translate into official sanction for the trade, fomenting vice and immorality (Obregón, 2002: 167.) In addition to Castañeda's report, Bogotá's municipal council approved the Ordenanza No. 53 del 13 de agosto de 1892. This ordinance established key provision regarding Bogotá's police and general sanitary measures in the capital (Moncada, 1998: 160–161). Ordinance No. 53 placed the burden of prophylaxis on the prostitute, locating the burden of prevention on the prostitute's diseased body. Article 2 targeted women and minors who lived outside of 'la patria potestad' and could not therefore enjoy the protection of a husband, father or an official household (male) head. It defined the prostitute as a deviant, unprotected woman, without a trade or an occupation (Moncada, 1998).

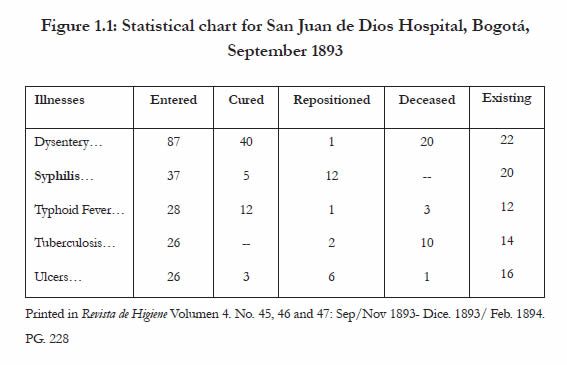

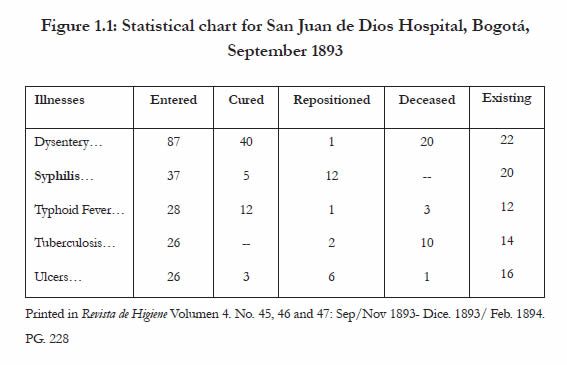

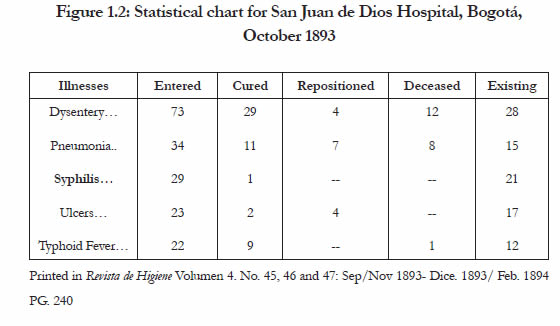

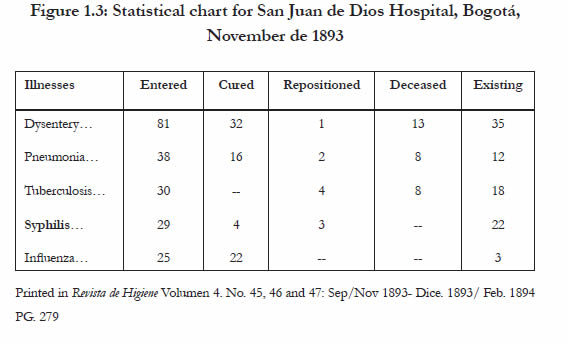

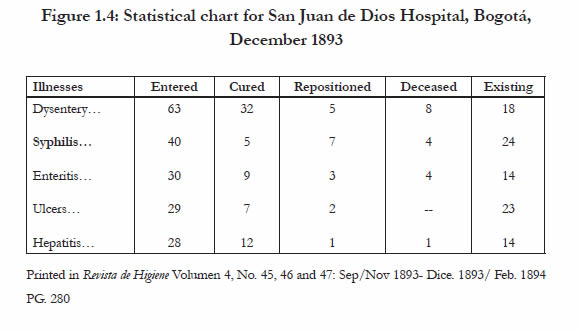

From 1886 to 1892, the Hospital de San Juan de Dios reported 2333 registered prostitutes, the majority of whom had been referred to the hospital by police authorities and treated for venereal infections, while a small percentage sought medical attention on a voluntary basis (Obregón, 2002: 167). Despite medical regulation of venereal disease and the establishment of government–sponsored programs of prophylaxis and treatment, the rate of venereal disease in the city did not subside. In 1893, syphilis continued to appear in statistics and medical charts as one of the city's leading causes of hospitalization (see figure 1.1 to 1.4) (Revista de Higiene, 1893). Statistics provided for the months of September through December 1893 indexed syphilis as a leading cause of hospitalization, second only to gastrointestinal conditions in Bogotá's Hospital de San Juan de Dios. Government approval of an extensive program of regulation would have to wait until 1907 (Obregón, 2002).

Over the next two decades public health campaigns against tuberculosis, alcoholism, and syphilis would continue to take center stage. The rise in rates of syphilis among infants was particularly worrisome. The rhetoric behind campaigns against venereal disease, the creation of anti–alcoholic leagues, and the regulation of prostitution expressed a common concern for the way in which the spread of these 'social diseases' affected children and the future of the Colombian nation. In the minds of hygiene experts, the relationship between alcoholism, prostitution and venereal disease continued to be closely intertwined. Fighting against one of these conditions, hygienists inadvertently fought all three social ills.

Living between constructed identities: Women, motherhood, prostitution and the gendered self

This article has examined distinct currents within a national discourse, comprised of a broadly defined political dimension and a more specific and narrow 'medical' construction of a society in crisis. In both of these instances gender became an essential component of elite and medical 'civilizing' discourses. Gender norms entered the discourse in the active creation of a national other, epitomized by the hysterical female body, the sexually deviant and promiscuous prostitute, the working class woman, and their social milieu. This piece has tried to provide a nuanced analysis of how female identities were deployed by medical doctors and hygienists as either a potentially threatening and degenerative to the nation's moral and economic fabric or as a 'civilizing force' through the mobilization of motherhood and the description of the Colombian family as a regenerative site. In direct contrast to the deviant other, civilized women were womanly, delicate, spiritual, and dedicated to their home. Civilized men were protectors of women and children. The construction of gendered indentities through the deployment of sexual pathologies helped to reinforce notions of a national other, categorically distinct from the country's ruling classes.

On the one hand, the creation of a feminine ideal in Colombia's national discourse equated 'civilization' and the achievement of order and progress with notions female identity that imagined women as angels of their home, arbiters of morality and keepers of their families. Colombian elites rhetorically highlighted their role within the family. Ideologies that viewed society as living organism–exposed to illness and vices in need of eradication or treatment– placed women and their maternal functions under close scrutiny. In essence turning women and their bodies into subjects of scientific study and tying their physical and moral health the nation's progress. Seen through the lens of elite constructions of the 'ideal' family, clear differences emerge between the private and the public–between house and street. Their rhetorical attempts to place women within the private sphere, assigned women the role of protecting the home as a private sanctuary and of watching over the morality of the nation. The doctors and government officials here examined, expected women to preserve the family as a unit and inculcate the values of order, hygiene and efficiency within the private sphere.

If elite constructions of 'ideal' female identities mobilized women in their primary function as mothers, preoccupations with the control of nonconforming sexualities that upset order or threatened the family unit, rhetorically emphasized female deviance. In direct contrast to the feminine ideal, the construction of the feminine other emphasized female moral transgression and sexual promiscuity. Since, ideal domesticity raised the value placed upon 'traditional' female roles, it simultaneously restricted the access of working–class and poor women to this idealized identity. The exaltation of female domestic roles and a full–time commitment to motherhood was not equally accessible to all women, cutting across class and racial boundaries.9 These commitments excluded poor women who worked for a living as domestic servants, textile workers, or day laborers, lived in consensual unions outside legally sanctioned marriage arrangements, or those who engaged in prostitution either on a full–time or part–time basis. These women could not aspire to the ideals prescribed by the ruling classes of women as 'angels of the home/ arbiters of morality.' The exclusion of these women from 'good society,' and their portrayal as immoral women subject to male sexual advances reinforced a double standard that rested on male permissiveness and female scrutiny. This double standard provided ample grounds for Colombia's ruling classes to equate female deviance and immorality with disease, bringing public women under scrutiny and their work under governmental regulation. In Colombia, regulation included the production of medical knowledge, the implementation of public health legislation, and the establishment of institutions of confinement and assistance by government officials, such as the syphilis ward in Bogotá's Hospital de San Juan de Dios. Attempts to institute social control measures became contested scenarios where the urban poor and medical professionals struggled over the definition of work, gender, and the making of a nation. Medical representations of disease and health related to the bodies of the poor were never one–sided. In their day–to–day contact, Colombia's lower classes, prostitutes and doctors changed how they constructed their social worlds and thus affected the trajectory of processes of 'modernization' and state formation.10

NOTAS

1 It is important to point out that although gender constructs are central to my analysis of Colombian society, the medicalization of gender also coincided with constructions of race and class as pathology within Colombia's medical discourse. A strict or artificial separation of gender as a category, without acknowledging the role of race and class in the creation of gendered subjects, runs the risk of clouding the social complexities inherent on the processes of identity formation.

2 Despite the tendency to read the claims of the authorities articulating these medical, literary, or political discourses as homogenous it is important to highlight that the resulting discourses cannot be understood as a coherent, unified whole or as ideologically cohesive and uniform. As Trigo (2000: 125) points out in his work, 'the body of the other is not a matter of fact. It is, instead, a discursive artifact that is specific to a time and place. It is a construct whose physicality is produced and is stake.' Its creation is therefore historically contingent.

3 For the purpose of defining positivism, I will employ historian Charles Hale succinct definition of the term cited in Claudia Agostoni's (2003) Monuments of Progress: Modernization and Public Health in Mexico City, 1876– 1910. According to Hale, this set of ideas commonly referred to as positivism, lacks an accepted definition. But, positivism in its philosophical sense is a theory of knowledge in which the scientific method represents man's only way of knowing. Its methods are observation, experimentation and the search for laws of phenomena and the relationship between them. As a set of social ideas, positivism argued that society was a developing organism, not a collection of individuals, and that the only effective way of studying society was through history. The key to the scientific management of society was to develop elites that could provide the leadership for social regeneration.

4 Although both these journals were primarily regional in scope, they featured articles and correspondence from medical doctors and hygiene boards in other sectors of the country. In addition to this, these two journals also frequently featured medical treatises and reports from international medical and hygiene conferences.

5 Several scholars have explored in detail this confration between midwifery and the western medical establishment in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. See for instance: Dain Borges (1993). For a more recent case study in Bolivia of the negotiation between miswives and post–revolutionary state see: Nicole Pacino (2012). For an excellent article on the creation of ideal female types in late nineteenth–century Mexico see: W. E. French (1992).

6 For an excellent article on the creation of ideal female types in late nineteenth–century Mexico see: W. E. French (1992).

7 For a discussion regarding the regulation of prostitution in Mexico during this period see: Bliss (2001), for Argentina see: Guy (1995), for Brazil see: Caulfield (2000).

8 French doctor Jean Alfred Fournier (1832–1914) first described congenital syphilis in 1883; his main contribution to medical science includes a number of publications, where he stressed the importance of treating syphilis and provided detailed treatments for the disease's progressive stages. His contribution to the medical study of syphilis was influential among international medical circles. In Colombia, prominent doctors often cited his findings and translated excerpts of his work found in La Revista Médica de Bogotá. In 1901, professor Fournier funded the Société Française de Prophylaxie Sanitaire et Moral (French society of Sanitary and Moral Prophylaxis).

9 For an in–depth analysis of how socially constructed ideas of decency, honor, and domesticity shaped and demarcated boundaries of inclusion and exclusion in society see Susan Suarez–Finlay's (1999) excellent study of late nineteenth and early twentieth–century Ponce in Puerto Rico.

10 For this study the sources analyzed did not permit an in depth study of the way in which Colombia's prostitutes and urban poor engaged in a these contested scenarios and processes of negotiation vis–à–vis medical professionals, government officials and the Colombian state. Recent scholarship for other Latin American nations does however acknowledge these processes of negotiation. For Mexico, see: Bliss (2001). For an excellent volume on processes of state formation on the ground, and the negotiation and contestation of state initiatives by popular groups see: G. Joseph and D. Nugent. (1994). Everyday Forms of State Formation: Revolution and the Negotiation of Rule in Modern Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press.

REFERENCIAS

Primary sources

Carta dirigida al Presidente de la Academia Nacional de Medicina en la Ciudad de Bogotá. Revista de Higiene, 11 (140).

Carvajal, M. (1919). Contribución a la lucha antialcohólica. Alcohol, alcoholismo y locura. Revista Médica de Bogotá, (441–443).

Castañeda, G.J. (1892). Informe de una Comisión. Revista de Higiene, 3 (35).

Estadística del Hospital de San Juan de Dios de Bogotá, en el mes de Septiembre, Octubre, Noviembre y Diciembre de 1893. Revista de Higiene, 4 (45, 46, 47).

García, P.M. (1921). Sobre la Campaña Antialcohólica. Revista de Higiene, 11 (140).

Gutiérrez, J.B. (1898). Embarazo Histérico. Revista Médica de Bogotá, (233).

Gutiérrez, R. (1886). Prefecto general de la Policía. 'Carta de Mayo 29' Dirigida a la Sociedad de Medicina y Ciencias Naturales. Revista Médica de Bogotá, 10 (108).

Henao, J.T. (1893). Antisepsia Obstétrica (Manizales). Revista Médica de Bogotá, (186).

Informe sobre el estado higiénico del matadero público (Septiembre de 1893). Revista de Higiene, (45).

Lobo, M.N. (1899). Reporte entregado en la sesión solemne del 19 de Julio de 1899. Revista Médica de Bogotá, (243).

Mensaje Publicitario, 'Grajeas Gelineau, contra la Epilepsia y los desórdenes menstruales'. Revista Médica de Bogotá, (200).

Michelsen, U.C. (1892). Informe del profesor Castañeda. Revista de Higiene, 3 (35).

Posada, A. (1886). Informe acerca de la Prostitución. Revista Médica de Bogotá, 10.

Resolución Número 146, Sobre la Campaña contra el Alcoholismo (1921). Revista de Higiene, (141).

Trizar, J.M., Tortello, D. y Bondenari, E.J. (1921). Profilaxis de las enfermedades venéreas en la Republica Argentina. Revista de Higiene, (133).

Secundary sources

Agostoni, C. (2002). Discurso Médico, Cultura Higiénica y la Mujer en la ciudad de México al cambio de siglo (XIX–XX). Estudios Mexicanos, 18 (1), 1–22.

Agostoni, C. (2003). Monuments of Progress: Modernization and Public Health in Mexico City, 1876–1910. Boulder, USA: University of Colorado Press.

Anderson, W. (2006). Colonial pathologies: American tropical medicine, race, and hygiene in the Philippines. Durnham, USA: Duke University Press.

Archila, M. (1995). Colombia 1900–1930: La búsqueda de la modernización. En M. Velásquez (Comp.), Las Mujeres en la Historia de Colombia, Tomo II (pp. 322–358). Bogotá, Colombia: Norma.

Armus, D. (2003). Disease in the history of modern Latin America: from malaria to AIDS. Durnham, USA: Duke University Press.

Arnold, D. (1993). Colonizing the body: state medicine and epidemic disease in nineteenth– century India. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press.

Bederman, G. (1995).Manliness & civilization: a cultural history of gender and race in the United States, 1880–1917. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Bliss, K. (2001). Compromised Positions: Prostitution, Public Health, and Gender Politics in Revolutionary Mexico City. University Park, USA: Pennsylvania University Press.

Briggs, C. (2004). Stories in the Time of Cholera: Racial profiling during a Medical Nightmare. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press.

Briggs, L. (2002). Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press.

Borges, D. (1993). Puffy, Ugly, Slothful, and Inert: Degeneration in Brazilian Social Thought, 1880–1940. Journal of Latin American Studies, 25.

Caulfield, S. (2000). In Defense of Honor: Gender, Sexuality and Nation in Early Twentieth Century Brazil. Durnham, USA: Duke University Press.

Chamberlin, J.E. y Gilman, S.L. (Eds.) (1985). Degeneration: the dark side of Progress. New York, USA: Columbia University Press.

Foucault, M. (1980). The History of Sexuality, vol. 1 an Introduction. New York, USA: Vintage Books.

French, W.E. (1992). Prostitutes and Guardian Angels: Women, Work and Family in Porfirian Mexico. Hispanic American Historical Review, 72 (4).

Guy, D.J. (1995). Sex and Danger in Buenos Aires: Prostitution, Family and Nation in Argentina. Lincoln, USA: University of Nebraska Press.

Johnson, L.L. y Lipsett–Rivera, S. (Eds.) (1998). The Faces of Honor: Sex, Shameand Violence in Colonial Latin America. Albuquerque, USA: University of New Mexico Press.

Londoño, P. (1995). El Ideal Femenino del siglo XIX en Colombia. En M. Velásquez (Comp.), Las Mujeres en la Historia de Colombia, Tomo III (pp. 302– 309). Bogotá, Colombia: Norma.

Márquez, J., Casas, A., y Estrada, V. (Eds.) (2004). La Lucha Antialcohólica en Bogotá: de la Chicha a la Cerveza. En Higienizar, Medicar, Gobernar: Historia Medicina y Sociedad en Colombia (pp. 159–182). Medellín, Colombia: Universidad Nacional.

Molina, N. (2006). Fit to Be Citizens? Public Health and Race in Los Angeles, 1879– 1939. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press.

Moncada, M. S. (1998). La Prostitución en Bogotá 1880–1920. Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y Cultura, 25.

Nóbrega, E. (1998). La Mujer y Los Cercos de la Modernización: Los discursos de la medicina y el aparato jurídico. Caracas, Venezuela: Torino.

Noguera, C.E.R. (1998). La Higiene como Política. Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y Cultura, (25).

Obregón, D. (1992). Sociedades Científicas en Colombia: La invención de una tradición. 1859 1936. Bogotá, Colombia: Banco de la República.

Obregón, D. (2002). Médicos Prostitución y Enfermedades Venéreas en Colombia, 1886–1951. En A. Martínez y P. Rodríguez (Comp.), Placer, Dinero y Pecado: Historia de la Prostitución en Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia: Aguilar.

Pacino, N. (2012). 'Prescription for the Nation: Public Health in post–revolutionary Bolivia 1952 to 1964'. PhD Dissertation, University of California.

Palacios, M. (2006). Between Legitimacy and Violence: A History of Colombia, 1875– 2002. Durham, USA: Duke University Press.

Rivera–Garza, C. (1995). The Masters of the Streets. Bodies, Power and Modernity in Mexico, 1867–1930. Dissertation Abstracts International, 56, 2377.

Rodgers, D.T. (1998). Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press.

Sánchez, O.L. (1998). Enfermas, Mentirosas y Temperamentales: La concepción médica del cuerpo femenino durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX en México. México D.F., México: Plaza y Valdés.

Scott, J.W. (1999). Gender and the Politics of History. New York, USA: Columbia University Press.

Shah, N. (2001). Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco's Chinatown. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press.

Sowell, D. (1992). The Early Colombian Labor Movement: artisans and politics in Bogotá 1832–1910. Philadelphia, USA: Temple University Press.

Stepan, N.L. (1991). The Hour of Eugenics: Race, Gender and Nation in Latin America. Ithaca, USA: Cornell University Press.

Suarez–Finlay, E. (1999). Imposing Decency: The Politics of Sexuality and Race in Puerto Rico, 1870–1920. Durham, USA: Duke University Press.

Trigo, B. (2000). Subjects of Crisis: Race and Gender as Disease in Latin America. Hanover, USA: Wesleyan University Press